Everything is as usual the day Janne Mai Lothe Eliassen leaves her family for good:

The curtains are drawn. The flat smells of cigarettes, alcohol and cat faeces. The floor is covered in rubbish. Her mother and younger brother Ronny are sitting on the couch, heavily intoxicated.

As Janne enters the living room, she feels something burst.

"Why is it so bright in here?" she asks.

She then falls to the ground, her body in cramps.

Knuckles and veins are showing under her yellowing skin. She looks like a prisoner of war, Ronny thinks.

Janne has fought for her family for 27 years. Fought against the violence and the drinking. Fought against her own body, a body her own mother called “ugly”. She has fought to be heard.

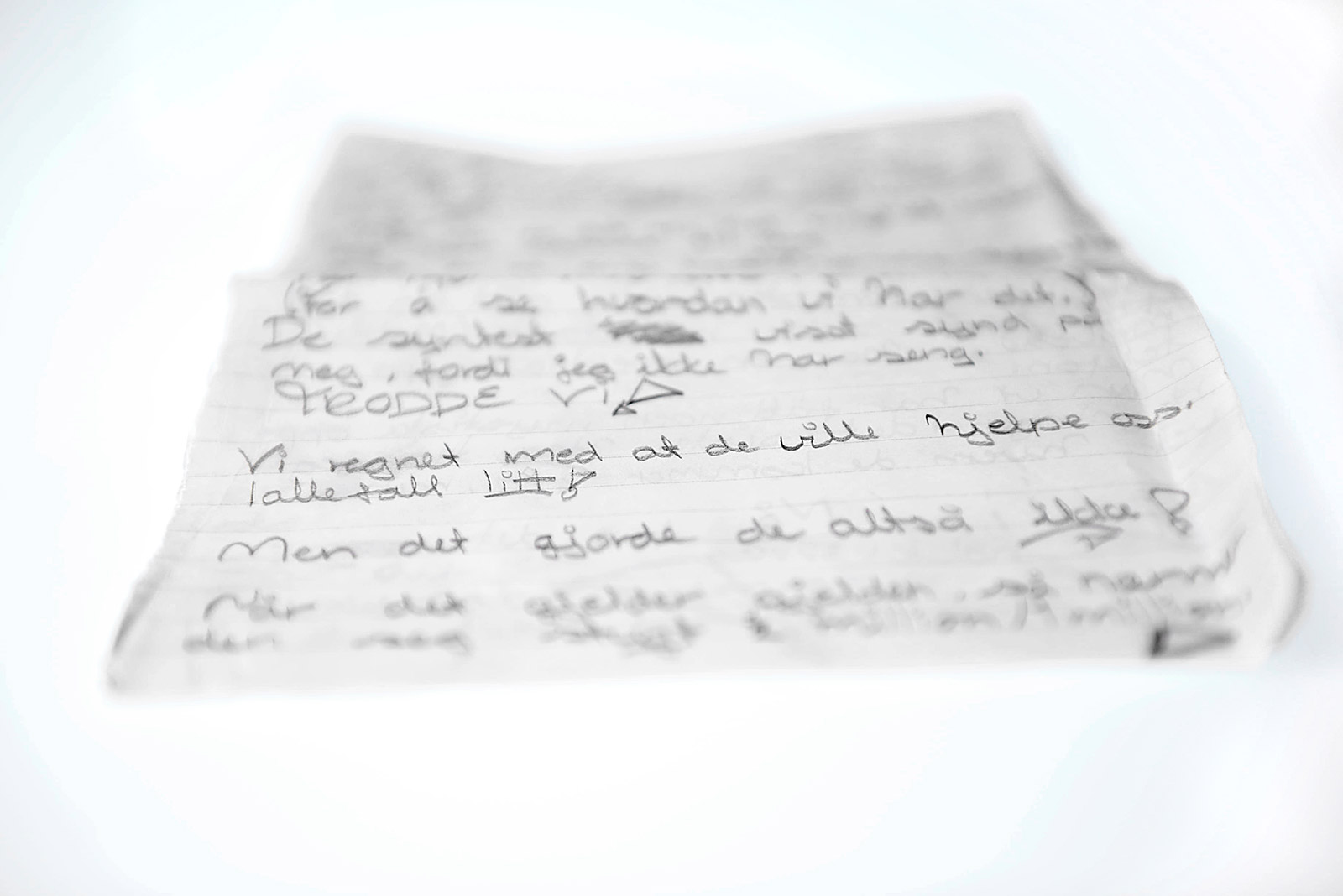

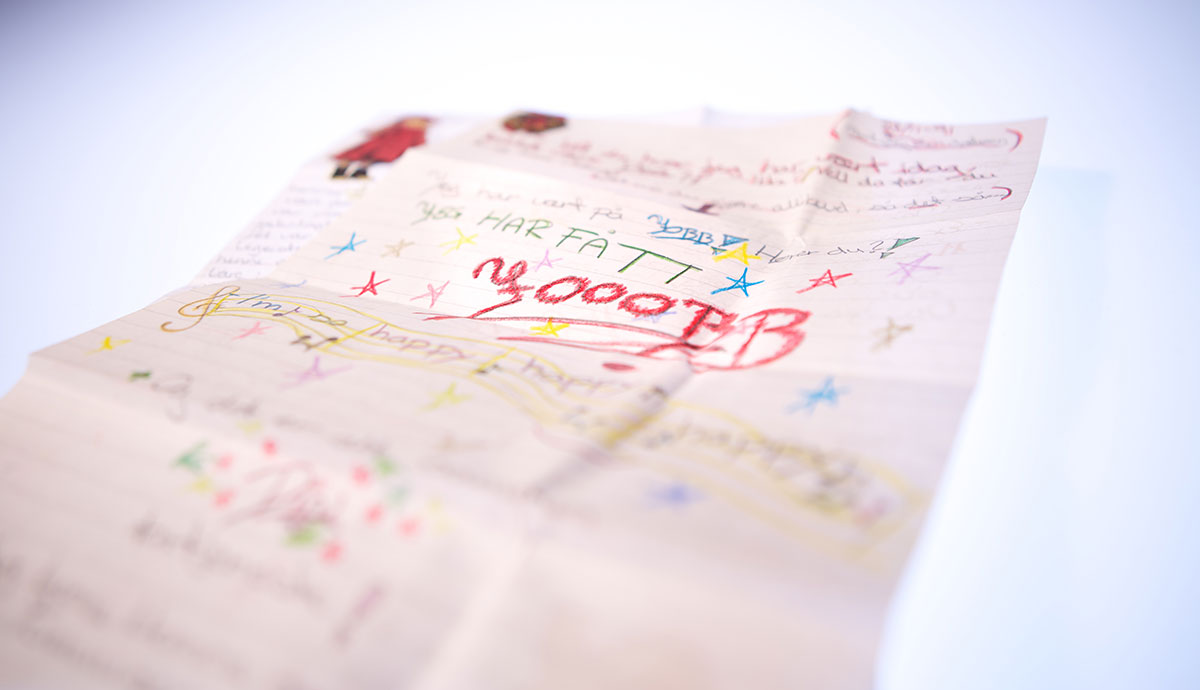

There has been no lack of warnings. Hundreds of letters of concern have been written about Janne and her family. Those who could have done something about the situation, knew about the circumstances.

And yet she is still here.

But today it's over.

Today her body gives in.

"Call an ambulance!" Ronny bellows and lunges towards his sister. Their mother does nothing.

Janne Mai Lothe Eliassen leaves home accompanied by sirens and emergency lights. During the short trip from Landås to Haukeland hospital, her life is hanging in the balance.

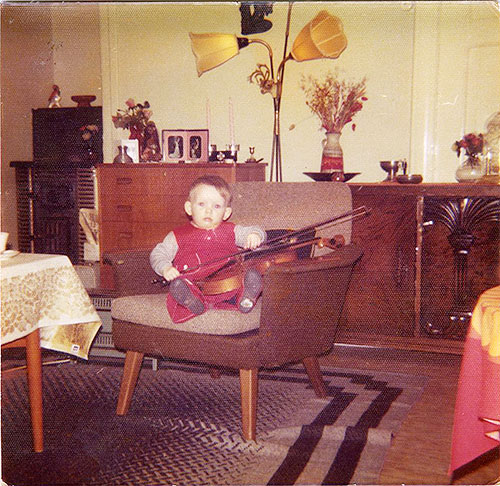

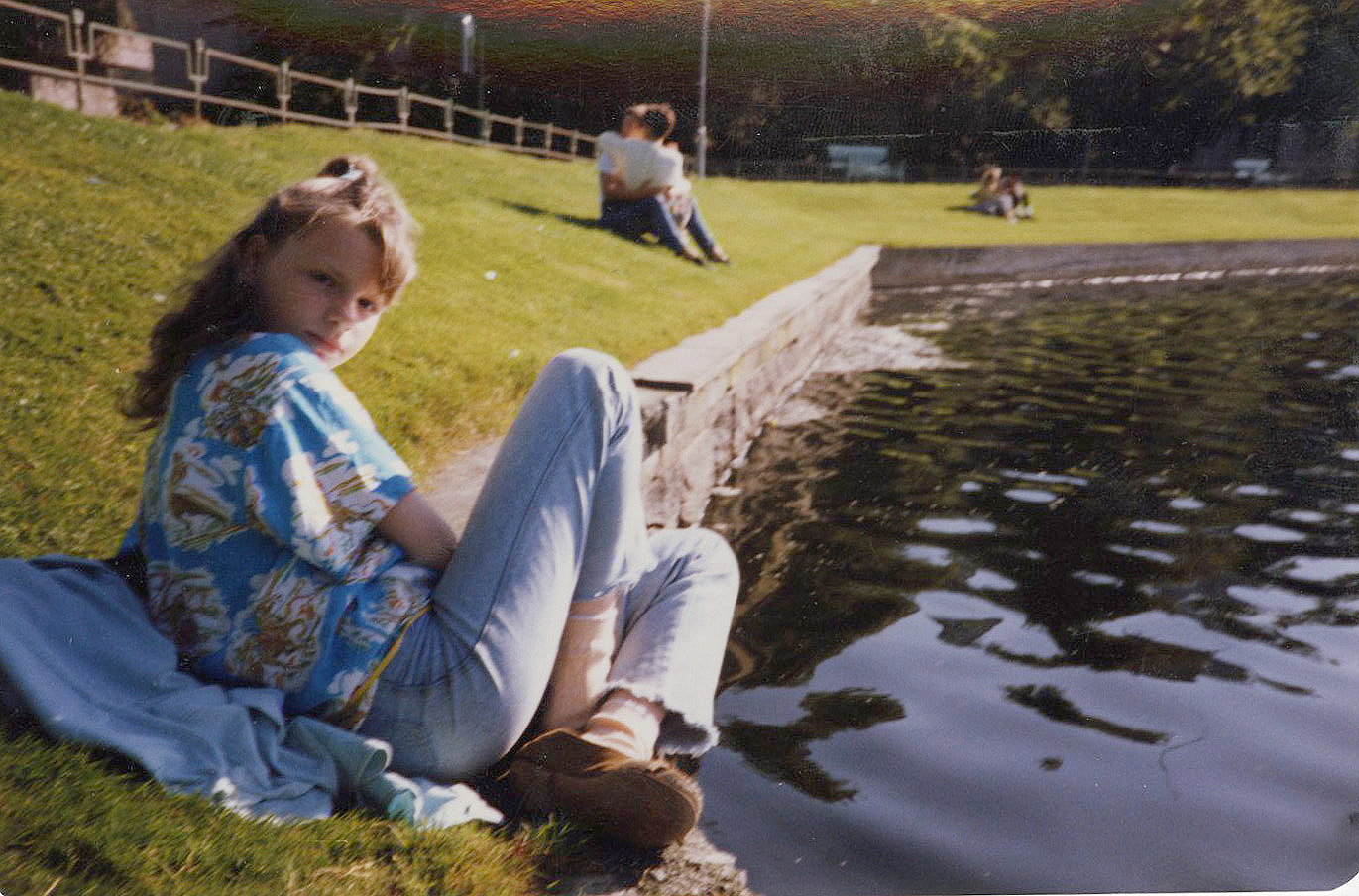

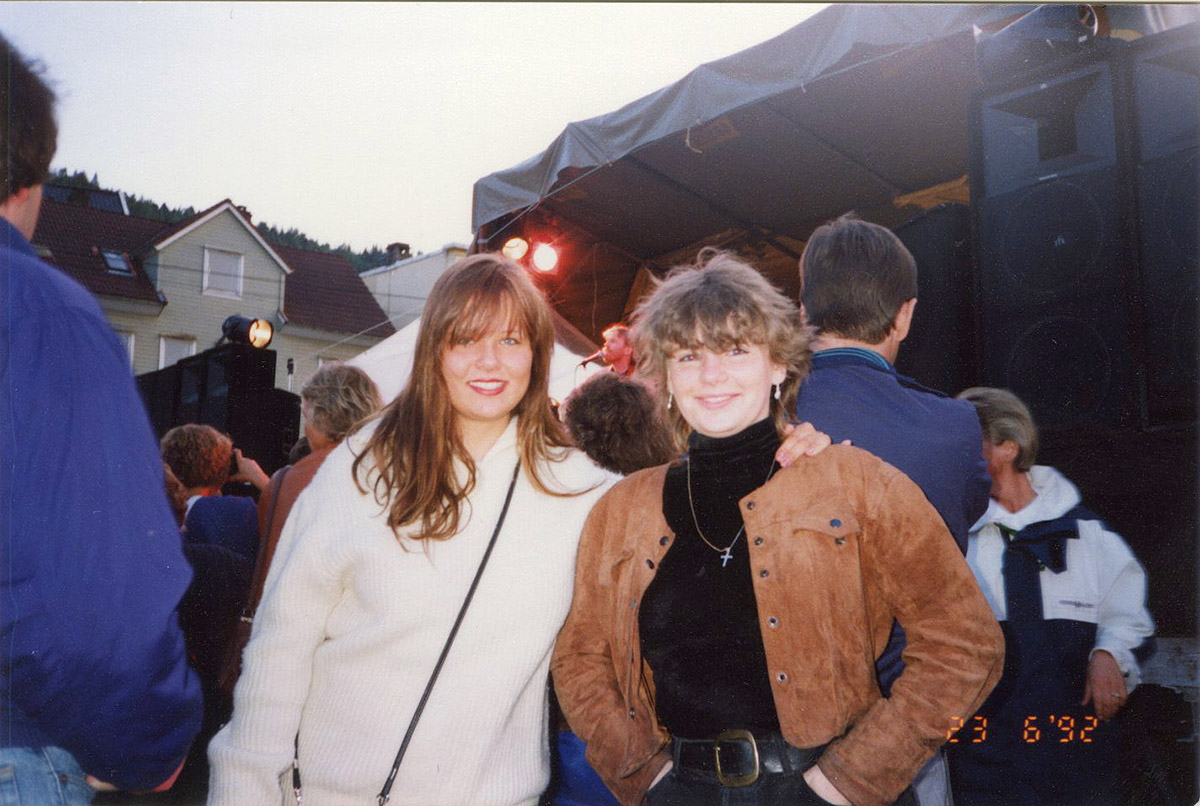

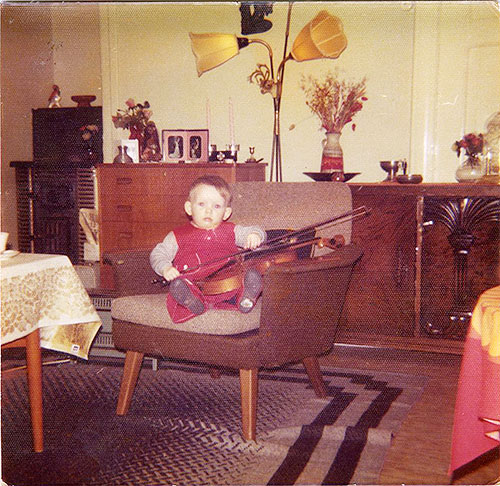

AT GRAN’S: Janne is one year old, in a chair in gran’s living room, holding a violin. Throughout their childhood Janne would bring her younger brother to their gran’s in Olsviksåsen when things became too heated at home.

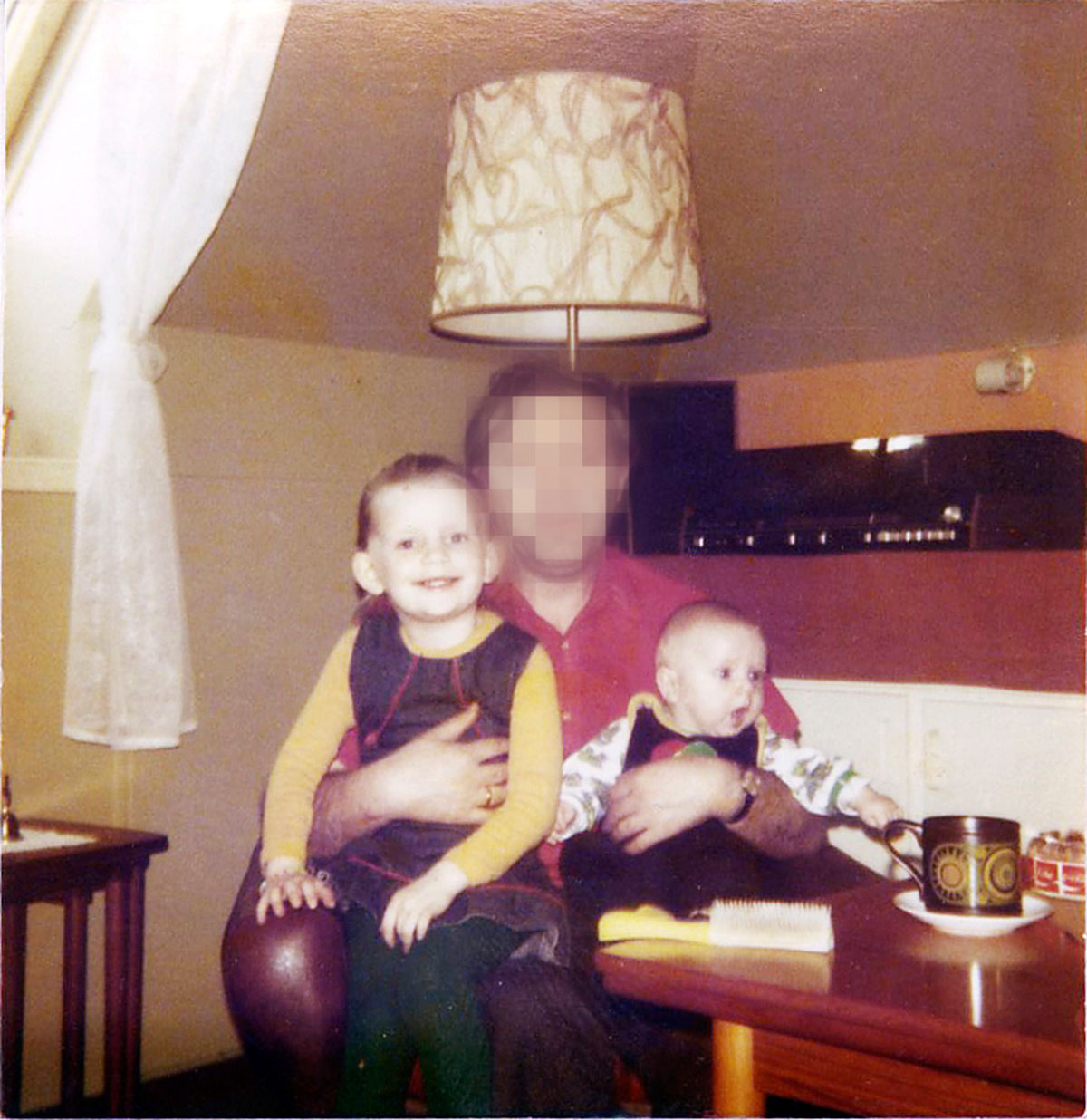

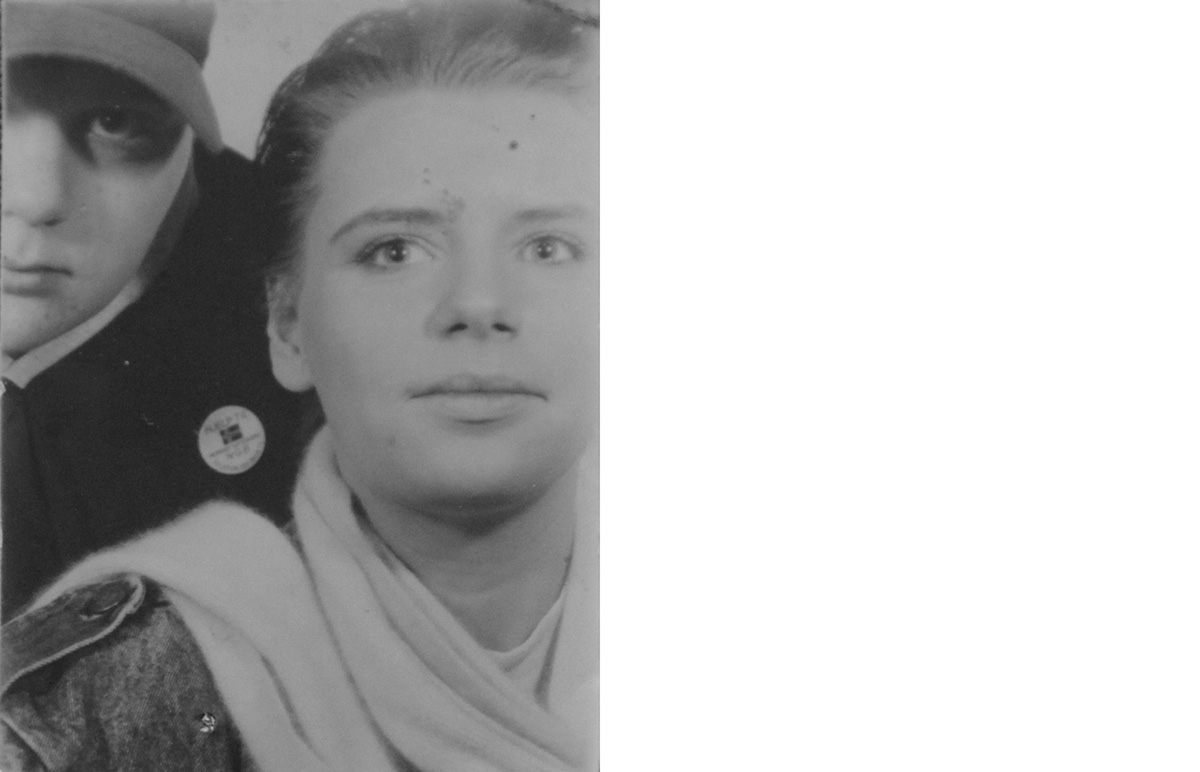

Janne Mai is born on 28 May 1973. The circumstances of the birth are not happy. Her mother is forty, homeless, and a heavy drinker. She doesn't tell anyone who the baby's father is.

At the Bergen Home for Mothers, children's nurse Bente Liland cares for the new-born girl. Liland will become one of many who recognise that something is wrong, and try to intervene. Liland becomes one of the people closest to the family.

What she sees makes her notify social services, which is also home to child protection services at this time.

Liland's letter of concern is one of many to come.

As years go by, numerous warnings about a family in deep crisis are sent off. At least fourteen people from thirteen different departments and institutions file reports about a lack of sufficient care.

They are not vague concerns, but reports about criminal offences and serious neglect.

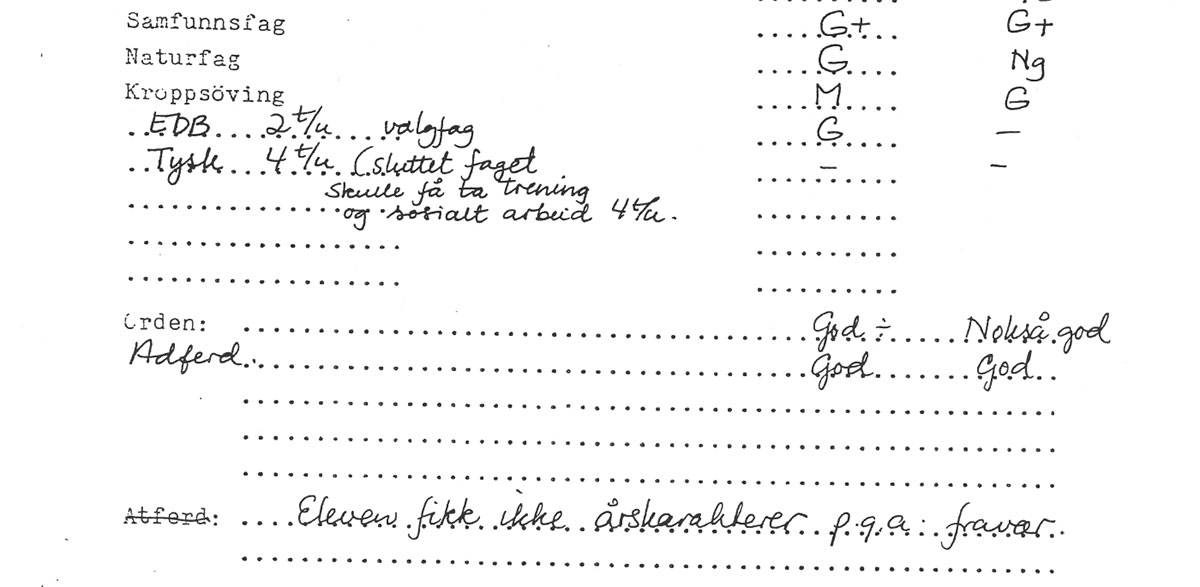

Janne and her younger brother are left without food for days on end. They turn up to school in dirty clothes that don't fit them. Often they don't turn up at all. As they grow older, injuries become more noticeable.

But social services let the children stay on at home.

Psychiatrist Carmen Escobar Kvitting, head of the Clinic for Psychiatric Care for Children and Youths at Haukeland University Hospital, was one of the people who repeatedly raised the alarm with child protection services. Kvitting has been released from confidentiality. She feels certain that child protection services should have taken over the care for the children.

"Janne's life was over many years ago. She just existed," says Kvitting.

Several times the parents' needs have been used as an argument for not interfering with the situation. The biological principle – that children are best off with their biological parents – is deemed more important. This view has guided the work of child protection services up until today. For Janne and Ronny it will have devastating consequences.

Reports show that a number of meetings were held concerning the family's problems. Kvitting attended many of these meetings.

“In this case, an entire council administration became paralysed by a physically and mentally ill mother. Many documents show that the support system felt sorry for this mother who wanted to care for her children, despite being sick and appearing to be dying,” she says.

Kvitting isn't alone in thinking along those lines. Many of the reports from the 1980s state “the mother appears to be dying.”

Janne’s and Ronny's mother passed away in 2010.

"Did you try to notify anyone?"

"I did. Lots of times."

"What should child protection services have done?"

"Listened to us."

Janne, 2013

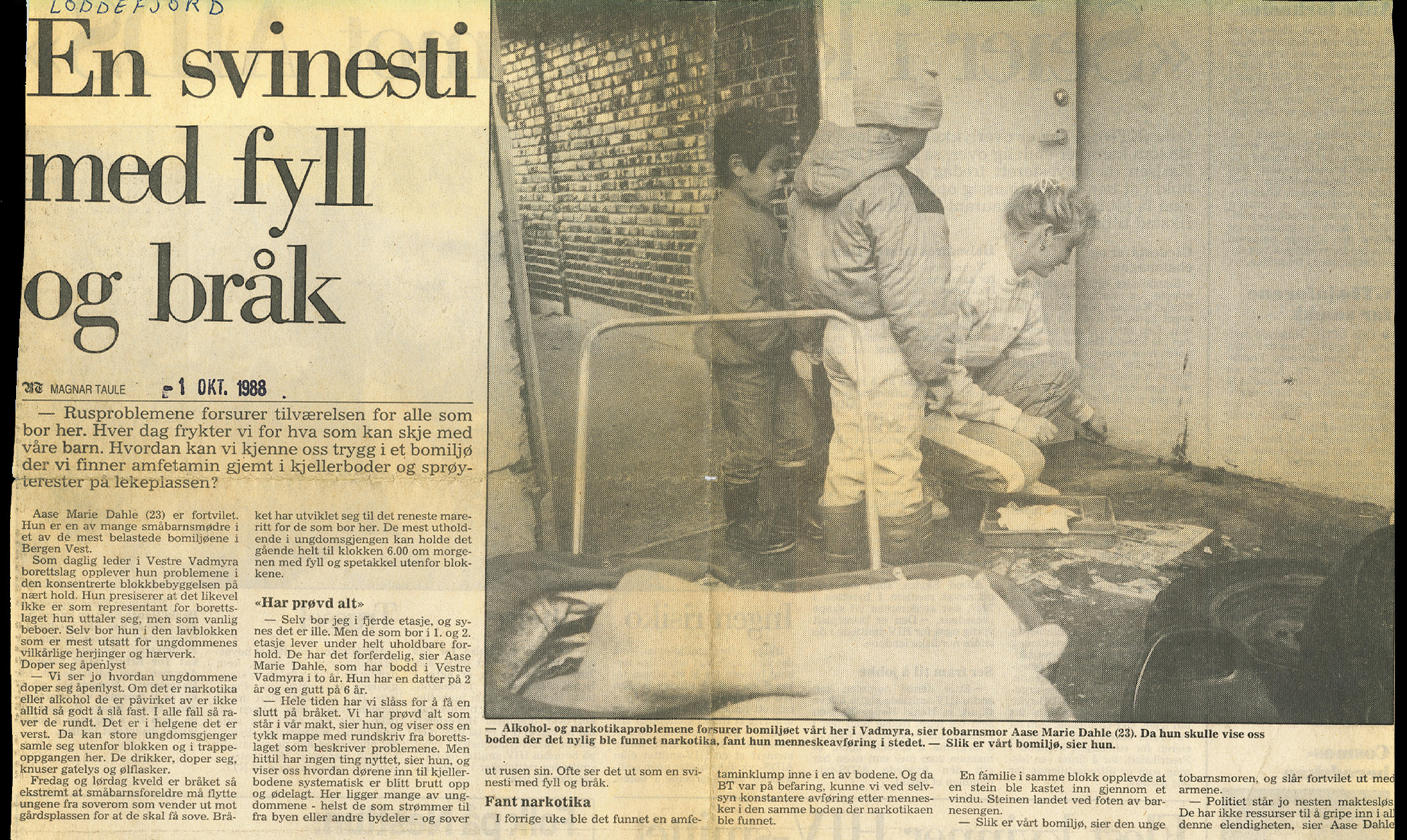

Throughout the 1980s Loddefjord is a borough in crisis. Children as young as fourteen are selling drugs outside the grey concrete high-rises.

At the offices of social services, files on families fighting addiction, psychiatric and financial problems are piling up. Staff are hard-pressed. A handful of case workers handle thousands of families.

Janne's family is one of them.

There's a pungent smell of mould, alcohol and tobacco throughout the flat. The radiator is broken, and there are cracks in the floorboards. The mother drinks continuously, her new husband more periodically. When drunk, they become angry and abusive. The stepfather hit harder and more frequently, Janne says today. His eyes go dark. He shouts that he is going to kill them.